December 1, 2025

Science Is like Magic, Just Real

ISTA physicists overcome a fundamental limitation of acoustic levitation with charge

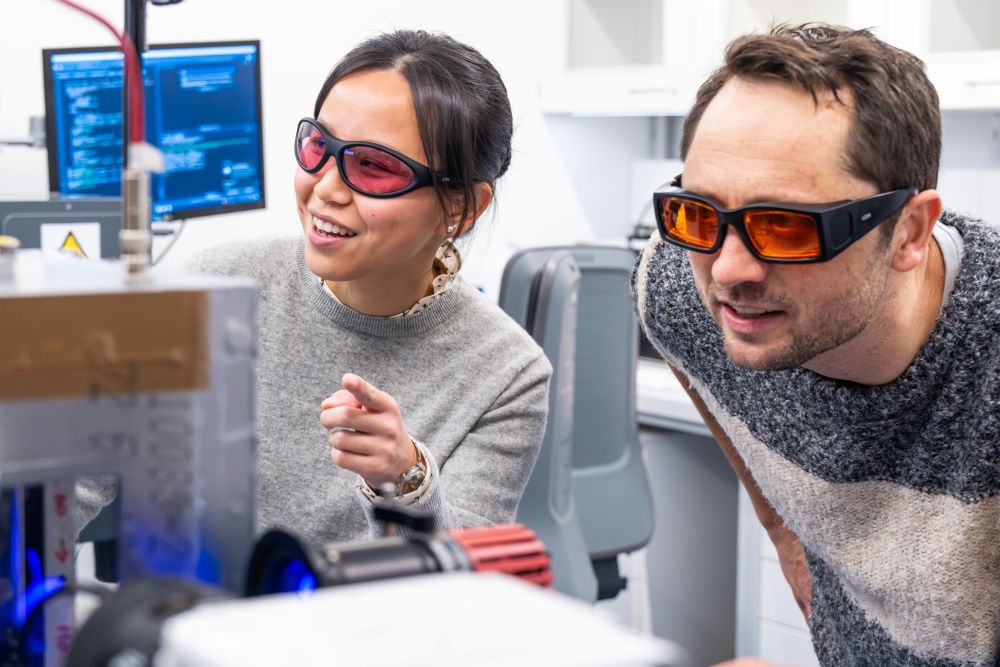

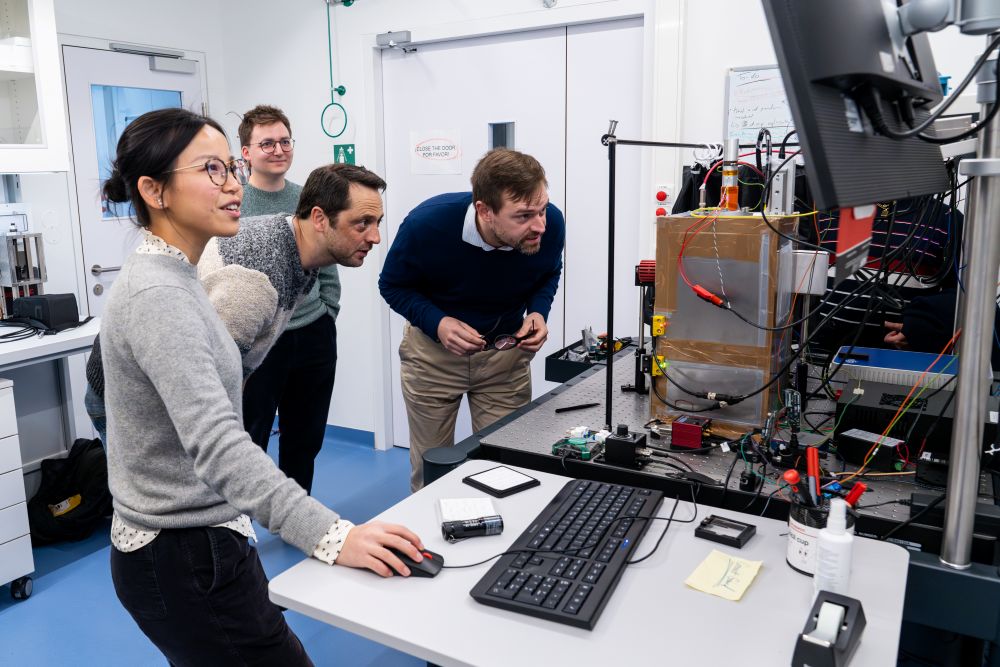

Physicists from the groups of Scott Waitukaitis and Carl Goodrich at the Institute of Science and Technology Austria (ISTA) have developed a method to acoustically levitate objects while keeping them physically separated using charge. Their results, published in PNAS, could find applications in materials science, robotics, and microengineering.

Who hasn’t dreamed of overcoming gravity and getting objects to hover above ground?

In 2013, Scott Waitukaitis, now an assistant professor at the Institute of Science and Technology Austria (ISTA), became interested in using acoustic levitation as a tool to study various physical phenomena. At that time, only a handful of research groups were using this technique for similar purposes. “While acoustic levitation was being used in acoustic holograms and volumetric displays, it was essentially geared toward applications. I had the impression that the technique could be used for much more fundamental purposes,” he says. After establishing his research group at ISTA, Waitukaitis started building several experiments based on controlling matter with sound.

Overcoming ‘acoustic collapse’

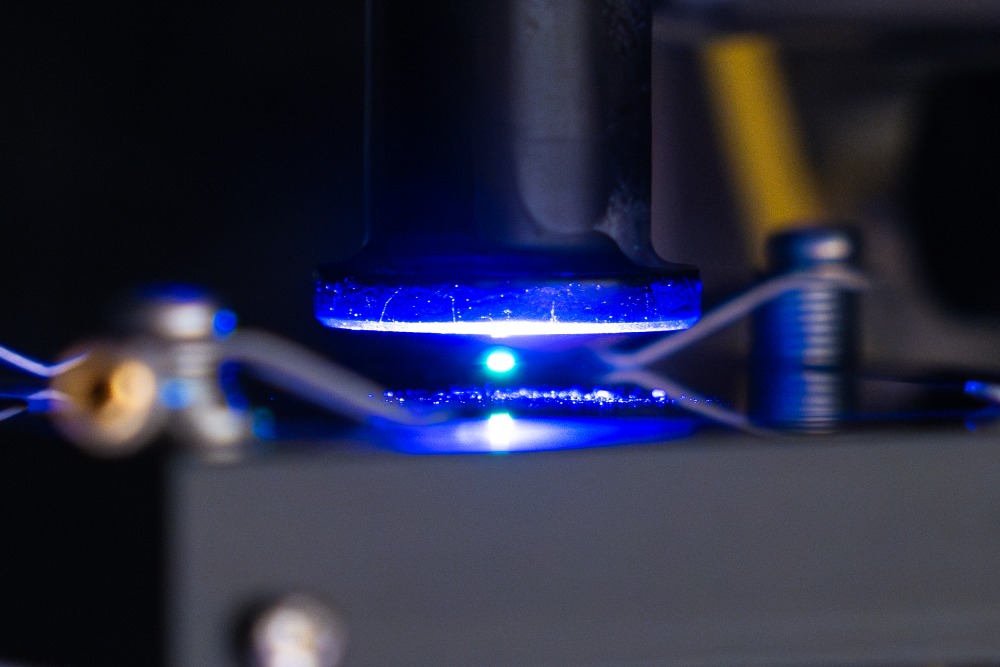

One curious aspect of acoustic levitation is that the method works well if a single particle is levitated, but if multiple particles are thrown into the mix, they snap together like magnets in mid-air. This ‘acoustic collapse’ occurs because the sound scattering off the particles creates attractive forces between them. It is a central limitation of the technique.

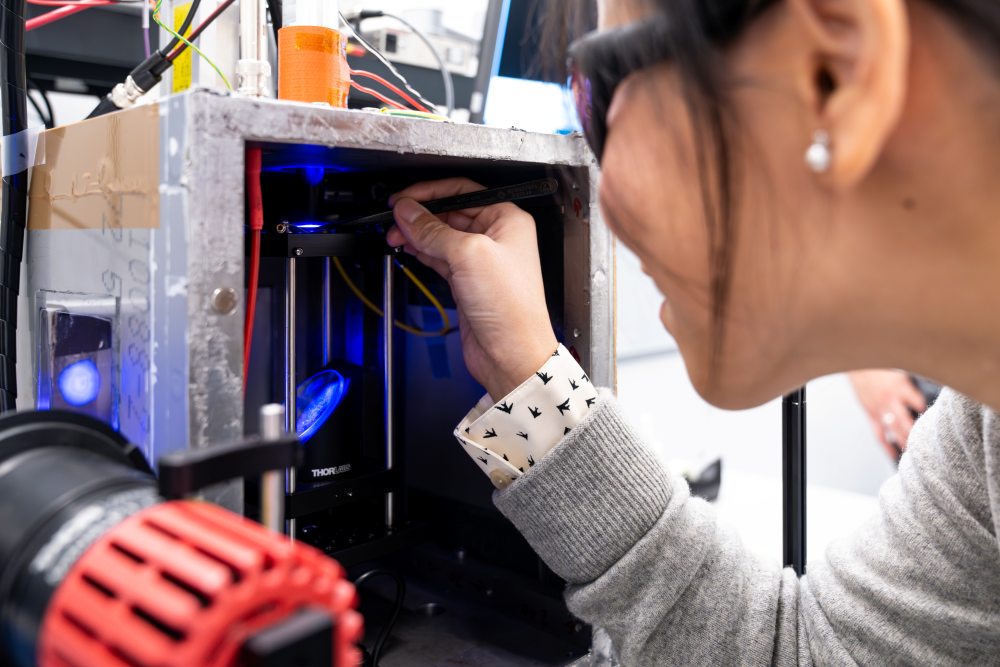

“Originally, we were trying to find a way to separate levitated particles so that they would form crystals—specific repetitive patterns,” says Sue Shi, a PhD student in the Waitukaitis group and the first author of the study. It was only later that they would realize that solving the collapse problem by separating particles was even more important. The key to this was adding another force to counteract collapse—enter electric charge and electrostatic repulsion. “By counteracting sound with electrostatic repulsion, we are able to keep the particles separated from one another,” says Shi.

After developing a method to charge the particles, the team found that they could tune the charge to levitate them with various configurations. These included completely separated particle systems, fully collapsed ones, and ‘hybrids’ in between with both separated and collapsed components. The scientists could also bounce the particles off the levitation setup’s charged bottom reflector plate to switch between the different configurations. Working with Carl Goodrich, assistant professor at ISTA, and PhD student Maximilian Hübl, the team developed simulations to explain all the configurations they saw, based on balancing sound-scattering and electrostatic forces.

‘Violating’ Newton’s law

As is often the case in science, phenomena that the team couldn’t have anticipated ended up being even more interesting.

Some of the complex behaviors they observed hinted at the presence of ‘non-reciprocal’ interactions, for example ones that ‘violate’ Newton’s third law. Foremost among these were certain particle arrangements that would spontaneously start rotating, or pairs of particles that would chase each other. Strictly speaking, Newton’s third law can’t be violated—the extra momentum gained by the particles is lost to the sound. Although prior theoretical work had already predicted that such effects should exist in acoustically levitated systems, observations were not possible, precisely because the particles would always collapse into a single clump. “You can’t study how individual particles interact when you can’t keep them apart,” explains Waitukaitis. “By introducing electrostatic repulsion, we can now maintain stable, well-separated structures. This finally gives us a controllable platform to investigate these subtle non-reciprocal effects.”

From frustration to fruition

The team’s method opens up new possibilities for manipulating matter in mid-air, with potential applications in materials science, micro-robotics, and other fields that rely on forming controlled, dynamic structures from small building blocks.

The team is already using their approach to study the non-reciprocal effects that it gives access to. “At first, it was frustrating to see these hybrid configurations and weird rotations and dynamics—they were preventing me from getting the clean, stable crystalline structures I was aiming for,” says Shi. However, presenting her results at conferences and seeing other scientists’ excitement helped her appreciate them as a fascinating phenomenon in their own right. “That’s the funny thing about experiments: the most interesting discoveries often come from the things that don’t go as planned.”

Science does come with a touch of magic.

In November, the American Physical Society announced Waitukaitis as the 2026 recipient of the Early Career Award for Soft Matter Research. He received this recognition “for resolving the core mystery of contact electrification and consistently bringing clarity and rigor to complex problems in soft matter through elegant and thoughtful experiments.”

Publication:

Sue Shi, Maximilian C. Hübl, Galien Grosjean, Carl P. Goodrich, and Scott R. Waitukaitis. 2025. Electrostatics overcome acoustic collapse to assemble, adapt, and activate levitated matter. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. DOI: 10.1073/pnas.2516865122

Funding information:

This research was supported by funding from the Gesellschaft für Forschungsförderung Niederösterreich under project FTI23-G-011.