April 17, 2023

“Research is simply captivating.”

New ISTA Professor Monika Henzinger on her research, career, and recent honor

In a ceremony today, the computer scientist Monika Henzinger was honored with the Austrian Cross of Honor for Science and Art in recognition of her work as part of the Austrian Science Council. Henzinger, who recently joined the faculty at the Institute of Science and Technology Austria (ISTA), is a renowned expert in algorithms with a wealth of experience in both academia and industry. ISTA Communications recently took the opportunity to sit down with Henzinger.

ISTA Comms: You just received the Austrian Cross of Honor for Science and Art—congratulations! Can you tell us a bit about why you were selected for this honor?

MH: For the last few years, I was part of the Austrian Science Council, an independent advisory body that seeks to optimize Austrian higher education and research. We created analyses, position papers, and recommendations for various governmental bodies—I led the development of an evaluation of Austria’s computer science landscape, including its current status and suggestions for improvement.

ISTA Comms: You were invited to join the council because of your background and expertise in Computer Science. Can you walk us through your career so far?

MH: I’ve had a varied career, working in both academia and industry. After a Master’s at the University of Saarland in Saarbrücken, Germany, I earned my PhD from Princeton University in the US, working on dynamic graph algorithms. Then, after several years as an assistant professor at Cornell University, I switched to industry—I was intrigued by web data mining, and you simply don’t have the resources to study that at a university. At first, I was at the Digital Equipment Corporation, and then I became the first head of Google Research. After that, I came back to academia to be a professor at EPFL in Switzerland, and since 2009 I’ve been a professor at the University of Vienna.

ISTA Comms: You’ve been at ISTA since March—what drew you to the Institute?

MH: At ISTA, I can focus on my research, which is what I love to do. The teaching load is significantly lower than at traditional universities, and the courses that are offered are all graduate-level. I am also looking forward to collaborating with some of my new colleagues, for example the Alistarh, Kwan, Lampert, and Pietrzak groups.

ISTA Comms: Tell us more about your research.

MH: Generally speaking, I currently work on dynamic algorithms and differential privacy. With the former, we develop algorithms that work efficiently even when the input changes—a common occurrence when dealing with real-world data. That is, if you update the input to a program, then our algorithms find a new solution more efficiently than starting from scratch with the new data.

The second is actually my main interest right now. The goal in differential privacy is to share information about a dataset while preserving the privacy of the individual data points. One example of a differentially private algorithm is a technique known as ‘randomized response’, which can be used to sum up numbers. Actually, this method comes from the social sciences to protect people when answering compromising questions. Essentially, ‘noise’ is added to an individual’s answers, protecting their data while ensuring that the responses overall are representative of the population, i.e., the almost correct sum can be computed from the noisy answers. In my work, I design differentially private algorithms for a variety of algorithmic questions that add as little noise as possible but offer maximum data protection.

ISTA Comms: With your work, you contribute to advancing digital privacy. What do you think about science’s role in addressing societal challenges like that?

MH: Not all parts of science can address societal challenges, at least not directly or immediately. I strongly feel that such fundamental research is also important. For example, in my work on algorithms for protecting the privacy of datasets, I frequently make use of theorems proved in the field of probability theory. But when these theorems were originally proved, the field of differential privacy did not even exist yet and nobody could envision how useful these theorems would be in the future. So both are needed, research that is more fundamental, not closely linked to a concrete societal problem and more applied research that can be used directly to address societal challenges.

In my work, I have alternated between the two. This is exactly what I find very exciting about research on differential privacy: It combines the two. There are many fundamental problems in this area that we do not yet understand, but it also has direct applications—Uber, Meta, Apple, Google, and many other companies already use differential privacy.

ISTA Comms: Is there a result that you are particularly proud of or excited by?

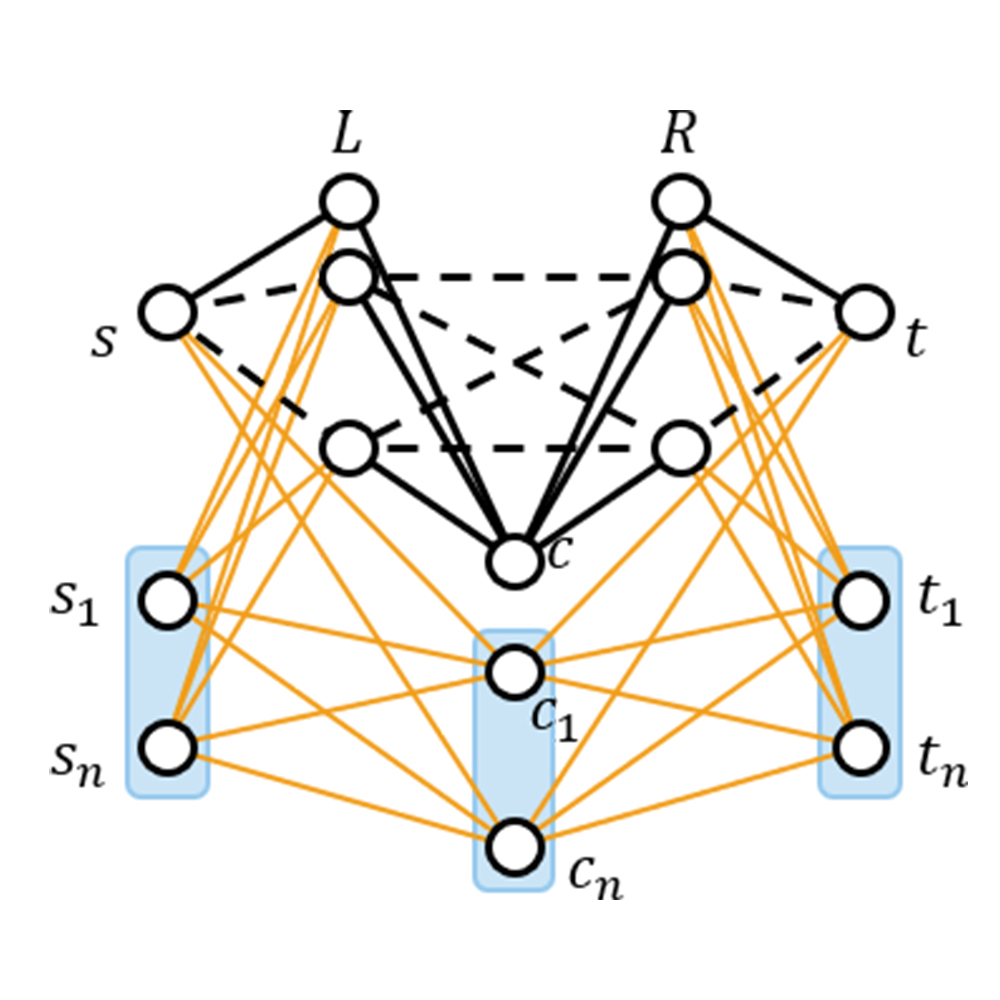

MH: I am proud of my work in dynamic graph algorithms. A graph is basically a network. Now assume the network can change, e.g. new connection links can be inserted, old ones can be deleted, and connection links can change in length. This is a dynamic network. I designed, for example, the fastest-known algorithms for maintaining almost-shortest paths in dynamic networks.

ISTA Comms: How do you do research? What does a “day in the life” look like for you?

MH: When I do research by myself, I need peace and quiet to fully concentrate. Usually, I try to do this in the morning. The afternoons are then reserved for meetings, for example, with students to listen to their ideas, point out mistakes or weaknesses, contribute my ideas, etc. When I work with a group, we try to find a week or so, where we spend all morning and afternoon in a conference room with a whiteboard. There, we present our ideas for new algorithms and correctness proofs for them to each other, find mistakes in these proof ideas, and try to learn from these mistakes to come up with a final proof that is correct.

ISTA Comms: What do you think people get wrong about Computer Science and its researchers?

MH: Many people think that being a computer scientist is a very lonely job because you just sit alone in front of the computer all day. In reality this is not the case. Usually the projects are so large that many computer scientists work together on it. Thus there is a lot of communication and joint problem solving involved. This is the case in industry as well as in academia.

ISTA Comms: How did you get interested in science and research?

MH: I’ve always been curious, and my parents have always supported me. What really got me hooked on research, though, were the popular science articles my French teacher shared with me when I was around 14 years old. That sparked my interest, and that’s when I knew I wanted to be a scientist.

ISTA Comms: What continues to drive you?

MH: Research is simply captivating—I just can’t stop. It’s the main way I contribute to the advancement of society.